Art of the Etched Singing Bowl

Share

February 22, 2024 - by Shakti

When etched bowls started flooding the market a few years ago, I passed them up because neither the quality of art, nor the bowls it adorned, were up to our Master-quality standards. Considering the extra cost that the etching work commanded, how could we justify the expense?

But a couple of years ago, I became inspired by the quality of art I was seeing at the home of one of my suppliers. Although the subjects were not always in keeping with traditional designs, I inquired if I could custom order designs for the Master-quality bowls I had selected. My supplier was happy to pass along our requests to the artist’s workshop, which, it turned out, was just one young family: that of Suraj Shrestha his wife Neha. They were the artists who fulfilled all of my supplier’s etched singing bowl orders exclusively.

We began to custom order designs, and Suraj’s artwork resonated with our customers. So for my September trip to Nepal, I had requested a visit to his workshop in Patan, the artistic center of traditional Newari arts, located in the former kingdom of Lalitpur.

Suraj (32) lives in a three-story home with Neha (28) and their 4 year-old son, Sujyan. The family welcomed us with characteristic Nepali hospitality. Neha graciously cooked and served vegetarian bean dumplings and a smoky local chai. The couple is emblematic of new Nepal, their livelihood rooted in Newari art, but they met on Facebook.

Having no formal training, Suraj became interested in art around the age of 14. His father passed away when he was 3, so he was raised in part by his grandfather, a Newari craftsman. So at an early age, Suraj was exposed to his grandfather’s work designing cast singing bowls and metal mala beads. Neha started producing art in 2012, and developed her natural talent for the work. Sujyan, while not taking pictures on the family smart phone, also practices the craft.

Having no formal training, Suraj became interested in art around the age of 14. His father passed away when he was 3, so he was raised in part by his grandfather, a Newari craftsman. So at an early age, Suraj was exposed to his grandfather’s work designing cast singing bowls and metal mala beads. Neha started producing art in 2012, and developed her natural talent for the work. Sujyan, while not taking pictures on the family smart phone, also practices the craft.

Suraj’s studio takes up the northeast corner of his living room, where he and Neha design and paint the bowls. Their operation also involves a two-burner kitchen stove and a walk-in sink in the southeast corner of their living room. They complete the final phase of the acid bath on their roof.

Since I had requested to document the entire etching process during my two-hour visit, Suraj selected a 12″ Ultibati which would not require etching on the outside due to its pitch-covered exterior wall. The interior of the bowl is harder to paint than the exterior, as it is difficult to angle the brush to navigate the curvature of the inside wall.

Suraj started the process with a freehand cross in the center of the bowl’s basin, over which he placed a small piece of electrician’s tape. The tape acts as an anchor for the point of his compass, which was outfitted with a paint brush. He uses the brush, dipped in a cooked down, thick petroleum solution, to sketch out the ascending rings up the bowl’s interior wall. Rotating the bowl on a lazy susan, he draws a series of lines from the base to about an inch below the rim. As he works, Neha continuously stirs the petroleum mixture to keep it from settling. Suraj refines the lines as he draws them, dabbing them with a cotton towel. Before long, he has drawn seven concentric circles in the basin, leaving approximately a six-inch space in the middle for a central image.

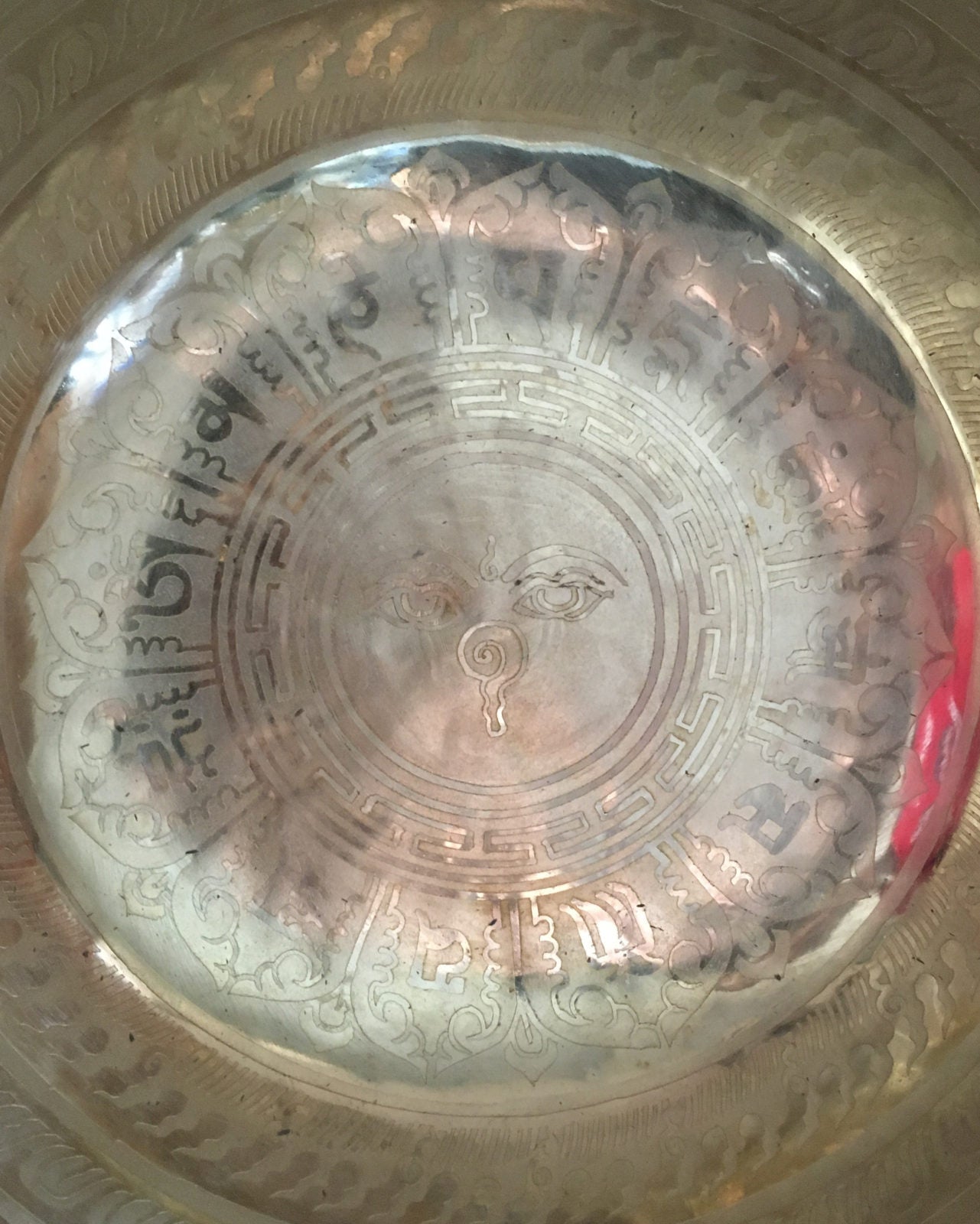

In this bowl’s case, Suraj has chosen the central image to be the Buddha’s Eyes, also known as the Wisdom Eyes. This iconic Nepali image depicts the Buddha’s eyes and Third Eye, as well as a stylized nose that is the same shape as the Nepali numeral one. This symbol signifies the unity of all existing phenomena. The image reminds us that the Buddha is always watching us and our actions. The image is pervasive in Nepal, from tourist products and car decals to the steeples of Buddhist Stupas. At this point, Suraj removes the tape, and paints the rest of the work on the bowl in freehand. To create the central image, Suraj first sketches the eyes, nose and third eye with a red pen, then expertly fills it in with his brush. The inner 6 concentric circles of the basin pattern become a Yantra pattern, a mystical, geometric diagram from the ancient Tantric tradition said to be energized by the deity.

In this bowl’s case, Suraj has chosen the central image to be the Buddha’s Eyes, also known as the Wisdom Eyes. This iconic Nepali image depicts the Buddha’s eyes and Third Eye, as well as a stylized nose that is the same shape as the Nepali numeral one. This symbol signifies the unity of all existing phenomena. The image reminds us that the Buddha is always watching us and our actions. The image is pervasive in Nepal, from tourist products and car decals to the steeples of Buddhist Stupas. At this point, Suraj removes the tape, and paints the rest of the work on the bowl in freehand. To create the central image, Suraj first sketches the eyes, nose and third eye with a red pen, then expertly fills it in with his brush. The inner 6 concentric circles of the basin pattern become a Yantra pattern, a mystical, geometric diagram from the ancient Tantric tradition said to be energized by the deity. Returning to his original red reference lines, Suraj fills in perfectly straight connecting lines of the mandala image, visually measuring the distance between them with precision. These spokes will become flower petal shapes that become the next element of the central image: 12 windows which will house repetitions of the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum. The windows feature billowing curtains, a classic design that can be found in Newari thangkas.

Returning to his original red reference lines, Suraj fills in perfectly straight connecting lines of the mandala image, visually measuring the distance between them with precision. These spokes will become flower petal shapes that become the next element of the central image: 12 windows which will house repetitions of the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum. The windows feature billowing curtains, a classic design that can be found in Newari thangkas.

To the next tier of the bowl’s inner wall, Suraj adds his signature ring of fire, representing protection from negativity. This is another traditional design component he integrates into most of his work. First he draws the outline of the fire, then fills in the lines within the flames. The next tier is rows of petals, and the top row contains a traditional foliate pattern. When I asked him the Nepali term for the pattern, he simply replied “grass” with a chuckle.

Now that the acid is painted on, Suraj inverts the bowl on the kitchen burner and bakes for about 5 minutes until it hardens. He then cools it in running water. From there, the operation relocates to the roof.

There are tubs of nitric acid of varying sizes all around, but as this bowl will be etched singing bowl only on the interior, Suraj pours the bright blue acid into the bowl up to the rim. After a 15 minute soak, he empties the solution out and scours the bowl until all of the petroleum is removed. The pattern is now visible on a shiny and golden interior surface.

There are tubs of nitric acid of varying sizes all around, but as this bowl will be etched singing bowl only on the interior, Suraj pours the bright blue acid into the bowl up to the rim. After a 15 minute soak, he empties the solution out and scours the bowl until all of the petroleum is removed. The pattern is now visible on a shiny and golden interior surface.

Now comes the antique color which provides contrast to the image. This is Neha’s expertise. She coats the bowl in sodium sulfide flakes, giving the golden bowl a bronze finish. She then adds a dark brown pitch, burnishing the patina and giving the pattern more definition. Their helper, Sharan Shreshta, paints a black pitch on the bowl’s exterior, and then gives the bowl a final wash. Displaying the bowl proudly, he poses with the family for a portrait.

Now comes the antique color which provides contrast to the image. This is Neha’s expertise. She coats the bowl in sodium sulfide flakes, giving the golden bowl a bronze finish. She then adds a dark brown pitch, burnishing the patina and giving the pattern more definition. Their helper, Sharan Shreshta, paints a black pitch on the bowl’s exterior, and then gives the bowl a final wash. Displaying the bowl proudly, he poses with the family for a portrait.

The pride the family puts into their work is so evident, and so worth it, in our opinion. The extra cost of our etched bowls are passed along to this family, and they lead a comfortable, middle-class life with a bright future. This is in keeping with Bodhisattva‘s corporate mission: to keep the traditional Newari crafts alive and preserved for future generations.

The pride the family puts into their work is so evident, and so worth it, in our opinion. The extra cost of our etched bowls are passed along to this family, and they lead a comfortable, middle-class life with a bright future. This is in keeping with Bodhisattva‘s corporate mission: to keep the traditional Newari crafts alive and preserved for future generations.